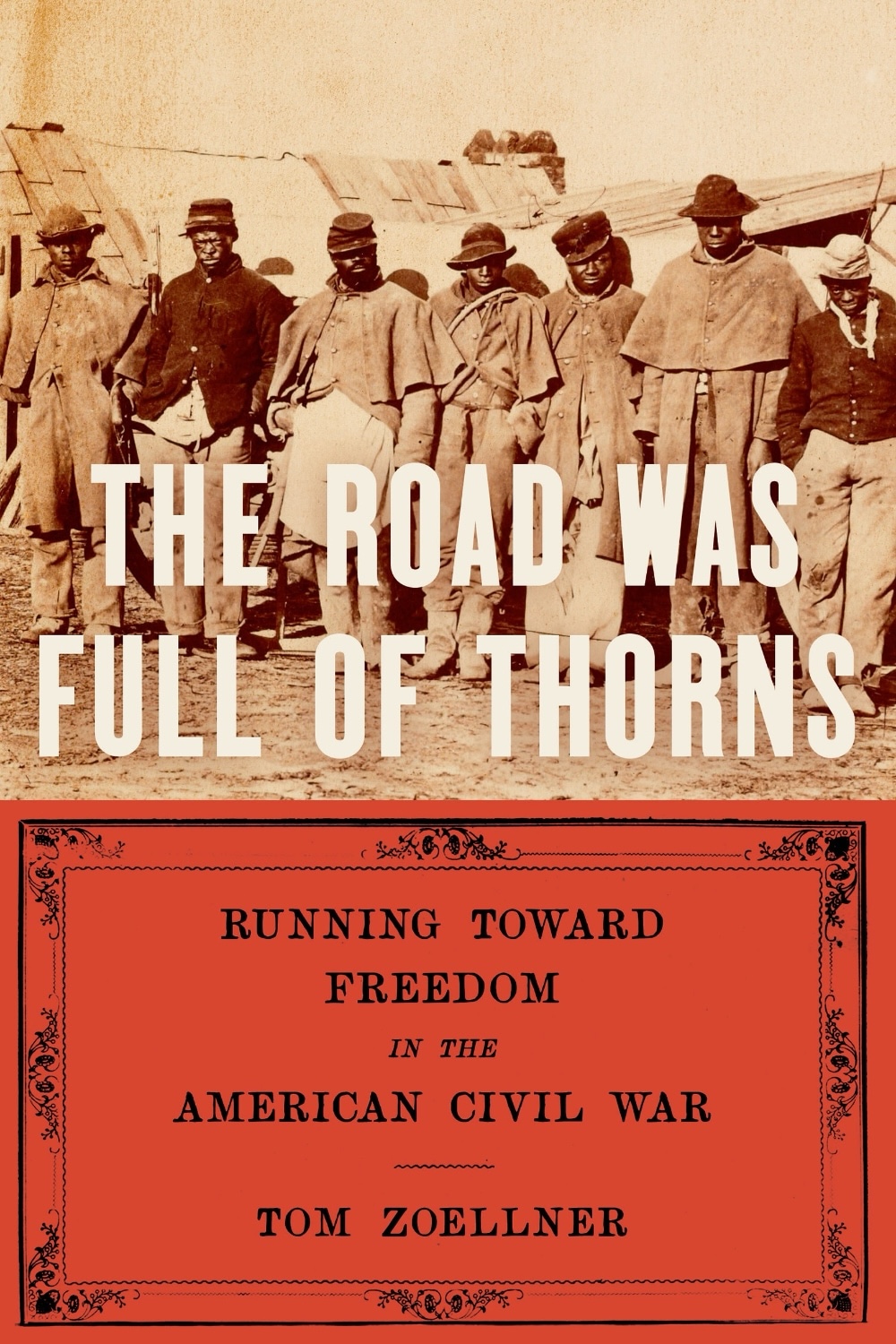

The Road Was Full Of Thorns. In the opening days of the Civil War, three enslaved men approached the gates of Fort Monroe, a U.S. military installation in Virginia. In a snap decision, the fort’s commander “confiscated” them as contraband of war.

The Road Was Full Of Thorns. In the opening days of the Civil War, three enslaved men approached the gates of Fort Monroe, a U.S. military installation in Virginia. In a snap decision, the fort’s commander “confiscated” them as contraband of war.

From then on, wherever the U.S. Army traveled, torrents of runaways rushed to secure their own freedom, a mass movement of 800,000 people—a fifth of the enslaved population of the South—that set the institution of slavery on a path to destruction.

In an engrossing work of narrative history, critically acclaimed historian Tom Zoellner introduces an unforgettable cast of characters whose stories will transform our popular understanding of how slavery ended. The Road Was Full of Thorns shows what emancipation looked and felt like for the people who made the desperate flight across dangerous territory: the taste of mud in the mouth, the terror of the slave patrols, and the fateful crossing into Union lines. Zoeller also reveals how the least powerful Americans changed the politics of war—forcing President Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation and opening the door to universal Black citizenship.

Order from Bookshop.org or The New Press.

There were oystermen and carpenters; fieldhands and house servants; most of them born into slavery and some who saw relatives for the first time in years among the muddy fields and torn tents of the camp sprawling outside Fort Monroe. Some of the arrivals, aiming for a homey feel, made small verandas of green boughs in front of their makeshift dwellings. Where they could find a patch of open ground, they planted gardens. Why had they come here, a visitor asked a group of refugees. “We wanted to do better, sir,” was the simple answer.

There was Jim Carey, a beautiful public speaker, who always drew a respectful crowd during prayer meetings when he preached of hell and salvation. During slavery, he had been allowed to sit in the balcony at a white church but once “got happy and shouted in a meeting” and was dragged out and threatened with thirty-nine lashes for his exuberance. When Lincoln was inaugurated, his angry master told him: “you are the cause of this,” and he replied calmly, “it is only what I have been expecting a long time.”

There was Sally Walker, who had labored for years as a house servant for William Ham and his wife, both ardent secessionists, who worshipped at St. John’s Episcopal Church and were fond of talking to their enslaved maid about spiritual matters. After Virginia seceded from the Union, Walker told Mrs. Ham she was praying that the Lord’s will would be done, and Mrs. Ham grew alarmed and insisted that the prayer in her house be altered to one for the success of Confederate President Jefferson Davis. “She was evidently afraid that the Lord’s will should be done,” remarked a man who met Walker in the crowds outside Fort Monroe. She had made her way out of the Ham household to freedom. A relative of hers, Thompson Walker, later insisted “we must trust in General Jesus, and not in armies and human arms.”

There was Robert Langley Brooks, a 17-year-old who had escaped from a Mathews County plantation more than fifty miles away, at a place called Winter Harbor where the soil was pancake-flat and often flooded. The native live oaks had been cut away to make boat hulls, and loblolly pines sprung up like weeds in the cleared fields. The year before, the master Jim Brooks had managed to raise $400 in corn by fertilizing the soggy ground with lime from oyster shells. Robert Langley Brooks lived in a one-room cabin with four others. When he heard he was going to be sold off and transported to the Deep South to pick cotton, he trusted the local rumors about the “Freedom Fort” to the south and stole away to join the refugees, paddling through the mouth of the York River in a stolen boat.

There was a 25-year-old man from the Eastern Shore of Virginia with a similar story. He told Robert Hamilton of the Anglo-African that he fled to Fort Monroe as soon as he could to avoid being moved or sold further South into the cotton states, and “they don’t think no more of separating us than a cow and calf.” The purpose of the war had been plain to him and his companions from the start. “We knew all about it,” he said. “We knew it was for the colored people.”

There was Joseph Corsey who found his way to the fort from a plantation five miles from Hampton where he often went all day with nothing to eat but huckleberries and horse sorrel, working so hard in the fields that his malnourishment caused him to stagger home like a drunk. He could still remember the day when he and about a dozen others secured a piece of steak about the size of a human hand, and they “would sop their bread on it until the last bit of bread was eaten,” greedy for every drop of protein.

There was Waddy Smith who walked in with useful military intelligence. “I came from York day before yesterday,” he told his debriefer. “I have been at work on the batteries. The batteries are on the right side of the road going toward York. There is another further one left field before you get to town.” They were guarded by one hundred and fifty militiamen, said Smith.

There was Edward Silence who had details of a skirmish on the James River involving the steamer Yorktown that he watched from a battery on Mulberry Island.

There was Israel Field who had been forced to whip his friends judged to be moving too slow, a terrible psychological torture. But this pain meant nothing to the enslaver James Downey for “the black man was a dog in his eye.” Field would be haunted the rest of his life by the sight of an elderly coach driver he had been ordered to lash 150 times until he lay bleeding and whimpering on the ground.

There was Caesar Stevenson whose master allowed him the opportunity to hire out for $150 but made his wife start work at 3 a.m. and refused to give their children any clothing until they were old enough to go to work themselves at the age of eight.

All of them had taken astonishing risks to get here. A correspondent from the New York Tribune watched as a group of enslaved people staggered into camp at Newport News after having rowed six miles “in open boats of the frailest sort” clinging to only a few meager possessions grabbed in haste. “It was a bold venture, that bordered on heroism,” he wrote, “a push for little less than life itself.”

.

Tom Zoellner is the New York Times bestselling author of nine nonfiction books, including Uranium Train and The Heartless Stone. He teaches at Chapman University and Dartmouth College. A former reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle, he is the editor-at-large at the Los Angeles Review of Books.